Warning: The following post contains spoilers. I didn't give away the climax of the film, but you'll definitely leave knowing more than you did coming in. Also, if you haven't seen the movie you may be confused by some of the references and/or so-called jokes made throughout. But then there's a good chance people who've seen the movie won't know what the hell I'm talking about either. Enjoy.

You know why I don't like karaoke? The song selection. They never have the right songs. And by "right," I mean songs that I consider to be in my wheelhouse (for the purposes of this intro, let's assume that I do, in fact, have a wheelhouse, even though, in reality, I of course do not). I've attended many a karaoke night, scouring the big, weathered song binders for songs that are up my alley. Wilco's Shot in the Arm. Pearl Jam's Footsteps. Anything off of Pinkerton. But alas, I always come up empty. The stuff they do have? It's sadly nothing in my skill range (again, assuming there is some subset of songs out there that actually falls within my vocal capacities...which, again, there is not). I am simply not versatile enough to pull off any of the songs they have at most karaoke nights.

You know why I don't like karaoke? The song selection. They never have the right songs. And by "right," I mean songs that I consider to be in my wheelhouse (for the purposes of this intro, let's assume that I do, in fact, have a wheelhouse, even though, in reality, I of course do not). I've attended many a karaoke night, scouring the big, weathered song binders for songs that are up my alley. Wilco's Shot in the Arm. Pearl Jam's Footsteps. Anything off of Pinkerton. But alas, I always come up empty. The stuff they do have? It's sadly nothing in my skill range (again, assuming there is some subset of songs out there that actually falls within my vocal capacities...which, again, there is not). I am simply not versatile enough to pull off any of the songs they have at most karaoke nights.

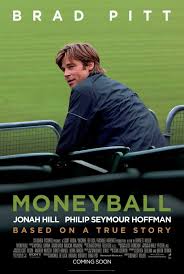

This is not a problem which I imagine Aaron Sorkin has. If I were compelled to picture Mr. Sorkin at a karaoke bar (and I apparently am so compelled), I imagine him as a confident, tie-loosened individual who gets up there and belts out everything from Sinatra to Bon Jovi to Adele to Kid Rock (note: I would pay good money to see Aaron Sorkin belt out Kid Rock). The guy can do it all. A Few Good Men, The American President, The West Wing, those are all well and good. Solid crowd pleasers that other people in the bar might be able to pull off (though not nearly as well). But then the dude breaks out a song about Facebook--the karaoke equivalent of reading the phone book--and he still blows the doors off the place. He follows that up with a little diddy about a baseball general manager and his chorus of stat geeks with economics degrees from Yale. And everyone loves that too! The guy has no limitations. I can't wait to see his next flick about a guy sitting on his couch staring at the wall, which is sure to become a riveting, heart-wrenching, movie of the year contender.

As if to reinforce this idea, the style of the film mirrors that of it's main character. Beane keeps the game at arms length and, for the most part, so does the movie. If you add up all the scenes of "live" Oakland A's baseball, you probably get about two and a half minutes worth of film (Hatteberg trying to field a grounder at first, Jeremy Giambi misjudging a fly ball in the outfield, and brief glimpses of an A's Royals game in September). The rest is presented through radio broadcasts, text messages, and tv footage (which, by the way, makes the A's Royals game they do highlight stand out all the more...nice touch there). What's more the portrayl is consistent with a core belief of sabermetrics; namely, that games are won and lost in the front office. The field is simply where all the various precalculated percentage receptacles put on uniforms and go play themselves out (as Pitt opines at one point, How can you not be romantic about baseball?).

As far as the receptacles (aka players) go, Chris Pratt and Stephen Bishop get some nice moments as Scott Hatteberg and David Justice (Pratt especially does a nice job playing dumbfounded during the scene in his living room, a talent he has no doubt honed during his time on Parks and Rec). But for the most part, the film is driven by two relationships: Billy Beane & Jonah Hill (Hill does a great job, but I can't remember the fake name they came up with to replace Paul DePodesta so let's just call his character Stat Guy), and Billy Beane & his daughter. Without the former, there is no movie; without the latter, I wouldn't still have that damn catchy Lenka song in my head a week after the fact.

The film does a nice job of portraying the Beane/Stat Guy dynamic as a partnership. Stat Guy might know more about the numbers, but there's never a sense that he's leading Beane around by the nose. For one thing, Beane doesn't always take Stat Guy's advice (i.e. Jeremy Giambi). For another, Stat Guy has a lot to learn when it comes to telling players they've been traded (from what I gather, you basically dump the whole mess on the team's traveling secretary and move on). And finally, Beane can teach Stat Guy some things about dealing with other general managers, as exemplified by the GM's masterful orchestration of a trade late in the movie (for any Sorkin fans out there, this scene was basically a series of walk and talks minus the walk, but with more telephones. Perhaps from now on we refer to this as a cell and tell? Yes? Wait, don't leave yet. Keep reading. I promise it's almost over.).

But for all the Billy Beane/Stat Guy buddy banter, it's Beane's daughter who gets the last word. Her song, besides being too adorable for words, is a ticking time bomb. Aaron "Cowboy Kid Rock" Sorkin arms it during the daughter's first jaw-dropping scene in the music store, and then he detonates it in the film's final frames to make sure nobody is leaving that theater bummed out by the otherwise somber ending. It's a manipulative, wonderfully effective maneuver that works in most part due to the choice of song. Lenka's The Show sounds as if it were engineered in a laboratory for the sole purpose of ending melancholy movies on a happy note. With a song that upbeat, the writers could've gotten away with damn near anything in the second to last scene. Billy Beane could've gone after Art Howe with a chainsaw (and really, who could blame him?). He could've packed Art's body into his Jeep, driven it out to the desert and buried it all the while mumbling "Hatteberg, not Pena. Hatteberg...not Pena." But as long as Brad Pitt gets back in his car, puts on his daughter's cd and starts driving, everyone in the theater heads home with a warm fuzzy feeling in their bellies. And that, my friends, is the magic of Aaron Sorkin (or whoever wrote the ending. I don't know. The movie had a lot of writers. Could've been one of the other ones. Sorkin can't write everything. He's got karaoke bars to get to.).

Rating: 8/10 Monocles

Pretzel Most Likely To Be Endorsed By Stat Guy: Snyder's Snaps. Let's face it, Stat Guy has trouble fitting in. He doesn't like 5-tool prospects. He is unable to wax creepily about the bodies of young high school boys like all the other scouts. It would be a sad cry for help if he were to start sucking down sunflower seeds just like everybody else. Stat Guy needs his own snack. Something that tells people, I too can exhibit a debilitating oral fixation while acquiring high levels of sodium, but on my own terms. Well Stat Guy, say hello to Snyder's Snaps. Geometrically sound, each pretzel looks like a miniature strike zone, just like the one you use to plot the pitches hitters see during their at bats! It's the perfect way to fill your belly while simultaneously sticking it to every Joe Morgan-loving yahoo of a scout who refuses to wake up and join the 21st century. Also, they taste great with sour cream!